ACCEPT a pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the police custody suite setting

ACCEPT: A pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the police custody suite setting

SPHR-SWP-ALC-WP2

01 April 2014

30 September 2016

30 September 2015

30 months

Alcohol, Brief Intervention, Feasibility, Trial, police, custody suite, behaviour change.

- Professor Eileen Kaner, Professor of Public Health & Primary Care Research (Fuse, Newcastle University)

N/A

- Dr Frauke Becker (Fuse, Newcastle – Health Economist),

- Dr Heather Brown (Fuse, Newcastle – Health Economist),

- Professor Alan Brennan (Sheffield University),

- Professor Matthew Hickman (Bristol University),

- Ms. Denise Howel (Fuse, Newcastle, Trial Statistician),

- Professor Dorothy Newbury-Birch (Fuse, Teesside University),

- Dr Ruth McGovern (Fuse, Newcastle, Brief Intervention lead)

- Current:

- Dr Michelle Addison (Project Manager)*,

- Colin Angus (Economics)*,

- Professor Simon Coulton (University of Kent),

- Dr Lisa Crowe (Qualitative researcher)*,

- Professor Eilish Gilvarry (Clinical Psychiatry)*,

- Dr Judi Kidger (Research Associate, Bristol University),

- Professor Elaine McColl (Trials input)*,

- Dr Muhammad Waqas (Health Economist)*

- Previous:

- Dr Colin Muirhead (statistician, retired)*,

- Ms. Jennifer Ferguson (Resigned post)*,

- Dr. Stephanie Scott (Changed role)*,

- * Collaborators based at Newcastle University

Project objectives

- To conduct a three arm pilot Cluster Randomised Control Trial (C-RCT) to assess the feasibility of a future definitive trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in police custody suites.

- To explore the acceptability of alcohol intervention and trial processes with staff and arrestees.

- To assess the fidelity of intervention delivery by Custody suite staff.

- To estimate the parameters for the design of a definitive C-RCT, including rates of eligibility, consent, recruitment, intervention delivery and participant retention at 6 and 12 months.

- To explore the scope for possible future data linkage between criminal justice and NHS data.

- To pilot the collection of cost and resource use data to inform a potential definitive trial.

- To use pre-specified stop:go criteria to determine is a future definitive trial is merited.

- If appropriate, to develop the protocol for a definitive C-RCT plus economic evaluation.

Changes to project objectives

In Bristol and Teesside, we recruited via Assessment and Intervention Referral Staff (AIRS) instead of detention officers, as staff arrangements differed in these sites. Thus we had an opportunity to assess which were best placed to deliver screening and brief alcohol intervention in custody suites.Brief summary

Methods

-

An external pilot feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial with three arms where interventions were delivered by custody suite staff as part of routine practice whilst processing arrestees. Cluster randomisation was used to avoid contamination due to staff delivering both control (screening only) and brief intervention conditions. A full trial protocol has been published [1].

Randomisation and allocation concealment: Custody suite staff were randomly allocated to one of three trial arms. The trial statistician wrote the Stata do file to perform the randomisation, but the randomisation sequence was generated by another statistician not involved in the study. Neither the trial statistician nor trial staff delivering training were aware of the allocation prior to the envelope being opened - in the staff member’s presence, immediately before training. Randomisation was stratified by site, with equal probabilities for the three arms and randomly generated varying block sizes. The arm to which staff were allocated was written in a note placed in a sealed opaque envelope, with a unique ID number written on the outside.

Study procedure and trial arms: Eligible arrestees were screened by trained staff via the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) [2]. The three (additive) trial arms were: screening only (control group); 10 minutes of manualised brief advice delivered by the person who carried out screening (intervention 1); and 20-minutes of brief (behaviour change) counselling delivered by trained alcohol counsellors (intervention 2).

Training: In two North East police forces, screening and brief advice was delivered by Detention Officers. In the third North East site and in Bristol, AIRS carried out screening and brief intervention delivery. Staff received training in line with their particular study condition. In all North East sites, a single Alcohol Counsellor delivered brief counselling (intervention 2) within one month of initial input. In Bristol, brief counselling was delivered on the same day by trained AIRS who had carried out the screening/brief advice.

Consent procedures: Arrestees were assessed for eligibility by custody suite staff. Eligible arrestees were asked to give verbal consent to be screened and provide anonymous demographic details. Only those who scored 8+ on AUDIT participated further, and all were asked to give written, informed consent plus contact details (address, telephone number, email) and their preferred mode of follow-up.

Success criteria: Recruit 60 cases per arm; successfully deliver interventions; follow up 50% of cases at 12 months (primary outcome follow-up point); confirm study procedures acceptable.

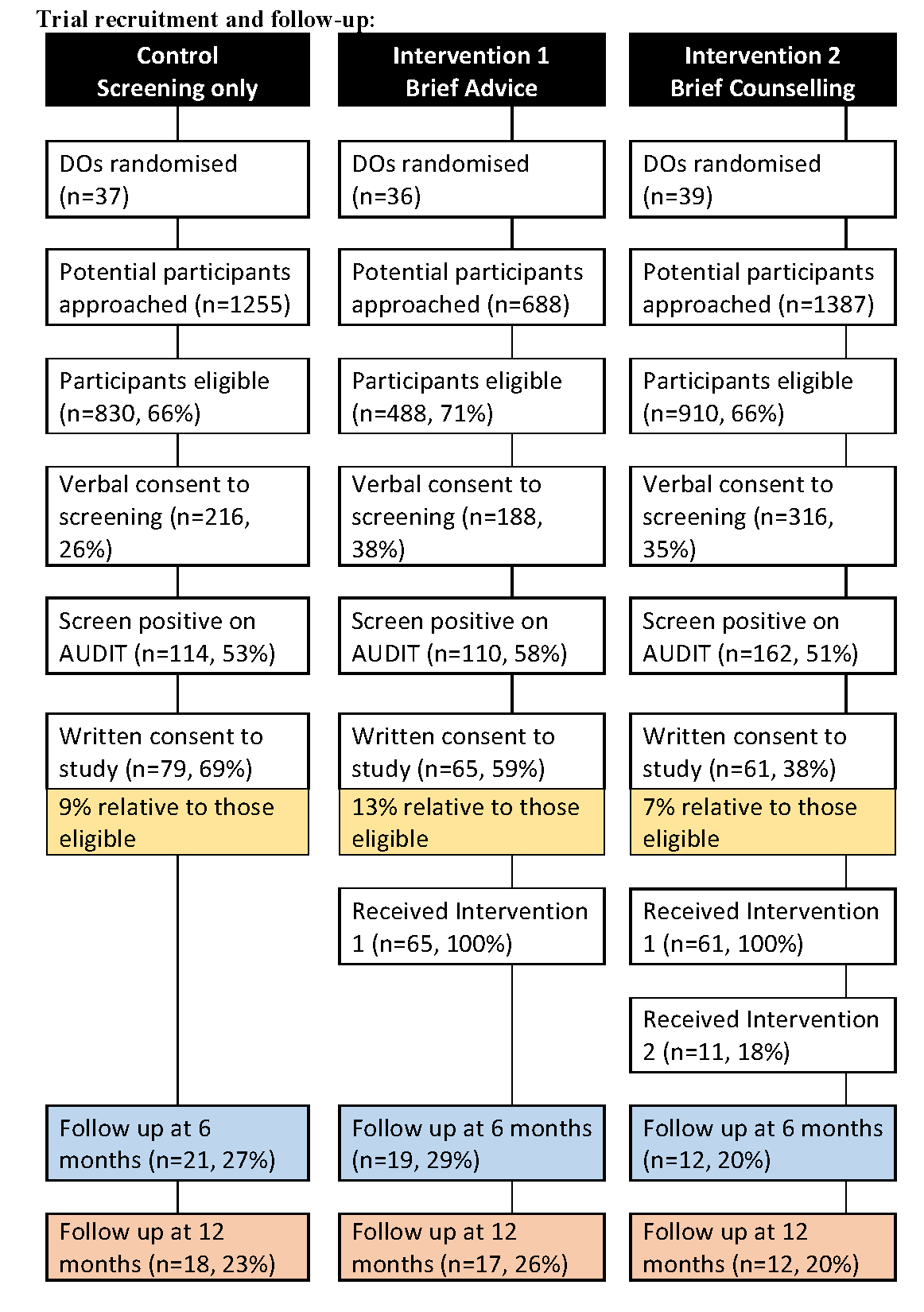

Trial recruitment and follow-up

Qualitative work: We interviewed 25 detention staff (after intervention delivery was completed) and 22 arrestees (most after 12 month follow-up; 7 were interviewed in prison). A key focus was to understand experiences within the trial and explore acceptability issues. All staff were interviewed in person and community-based arrestees were interviewed by telephone. These interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. We were not permitted to take audio-recording equipment into prisons and so these data were recorded via written note made during the interviews.

Results: Overall, 3,330 arrestees were approached and 2,228 (67%) were eligible to be screened. Of these individuals, 720 (32%) provided verbal consent for screening and 386 (54%) were screened positively; 205 (53%) provided signed consent to be enrolled in the study. Staff varied in the number of arrestees they contributed to the trial (range 0 to 25); the mean number of arrestees screened was 44; and the mean number of cases enrolled was 4.

Primary Outcomes: We enrolled: 79 controls; 65 intervention 1 cases; and 61 intervention 2 cases. The majority of the sample were white (94%), male (83%), had a median age of 31 (IQR 24-40) and educated to GCSE standard (42%) or below (35%); 73% were current smokers and 30% were seeking work. Mean AUDIT score was 22 (SD 10) and median was 20 (IQR 13 to 30). In terms of risk status, 34% were hazardous, 16% were harmful and 50% were potentially dependent drinkers. Just 20% of arrestees reported that they had ‘never thought about changing their drinking’.

Intervention delivery: Screening and brief advice were delivered to all of Intervention 1 and 2 cases but only 18% of relevant arrestees (n=11) received brief counselling; the majority were Bristol where it was delivered immediately after screening/brief advice.

Follow-up: Due to anticipated uncertainty about the mobility/traceability of our study group, a 6-month follow-up point enabled assessment of interim attrition. Follow up rates were 29% at 6 months and 26% at 12 months; contact by telephone was most successful (61% of those successfully followed up at 6 months and 60% of those at 12 months).

Qualitative data: Trial processes appeared to be broadly acceptable to staff and arrestees as the following quote exemplified: ‘I thought if I can give any help that might make people understand certain things and situations that maybe I have been through or whatever it might help’. However, we only interviewed arrestees who consented to the trial, so their views may not be typical. Custody Suite Staff reported mixed views about involvement in health focused intervention work. Some were enthusiastic and others felt either too busy or pessimistic about its impact and preferred the idea of referring arrestees to other staff (e.g trained counsellors). Moreover, arrestees’ motivation to participate varied as one explained: ‘He actually came to the cell and said to us, “You can either stop in here for ten minutes or you can come out with me and fill this questionnaire out.” I said, “Right, I’m coming out.”’. We were not told of any instances of perceived coercion to participate by arrestees. Nonetheless, it was clear that there may have been reticence on the part of some arrestees to provide contact details, as one staff member explained: ‘If they scored over eight, which most people did, probably including me, they weren’t really willing to give their details, I don’t know whether that was because they thought it was something to do with the police. Like I said, I did explain, “Give us your name, give us your phone number, your email address, address,” or whatever, “No, I don’t want that.” They might have thought, “I’ll get hassled constantly, people won’t leave us alone,” I tried to show them that probably wouldn’t happen but again, I think once they come in here they’re a bit suspicious about, “Hold on, hold on, if I’m a drug user as well and the police come round and there are people knocking on my door asking to speak to us, are they going to find something that they shouldn’t?”’ Finally, some arrestees reported that the follow-up procedures did make them think about their drinking behaviour: ‘It was that odd call every few months, they’ll say, “Just seeing how you’re doing, how’s your drinking and stuff,” and answering the same questions. I guess it made me think about it more every time they did call.’

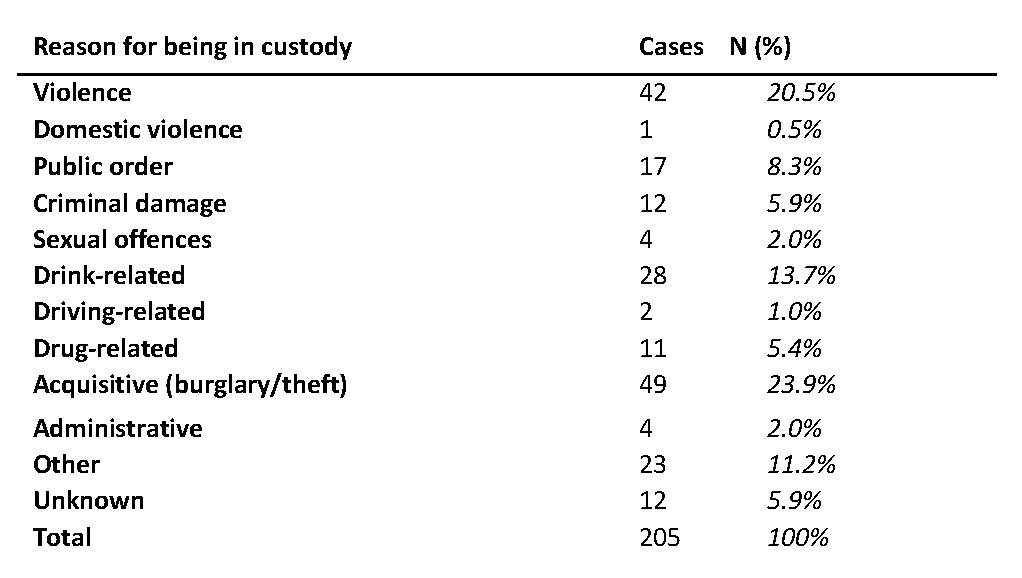

Secondary Outcomes: At screening, the reason for the arrest was recorded by staff and subsequent analysis showed a similar profile for arrestees in the trial and those who declined to participate (via anonymous screening data). For trial participants, the most common reasons for being in custody were violent (20% compared with 22% for non-participants) or acquisitive offences (24% compared to 28% for non-participants).

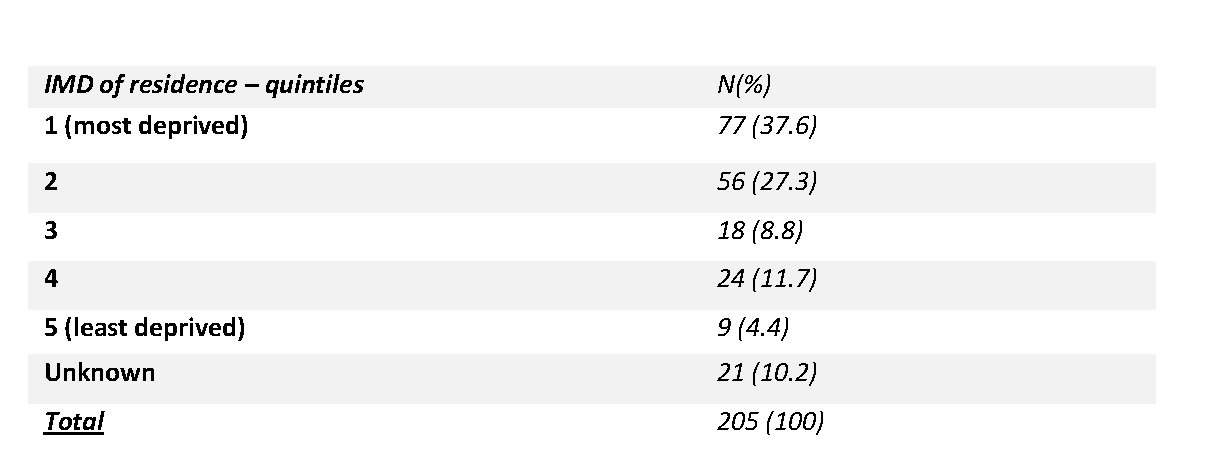

Data linkage: Permission was given by 193 (94%) arrestees at baseline for linkage to police force data. Using data sharing protocols that were agreed with senior police staff in each force area, we obtained arrest/re-arrest data for 93% of cases in the trial (n=192). This was possible via a Criminal Record Number (CRN) allocated to each offence committed by an arrestee. All CRNs are linked together by a Serial Record Number (SRN), unique to each arrestee, which operates only within each force area. Arrest data were obtained for a 24 month period (12 months before the study including the index offence that brought arrestees into the custody suite and 12 months after intervention). We were also able to re-check ‘current’ contact details for some arrestees who had moved since the study began and confirm postcode data which enabled us to calculate index of multiple deprivation scores (IMD, 2015); 65% of the sample lived in the two most deprived area quintiles in England.

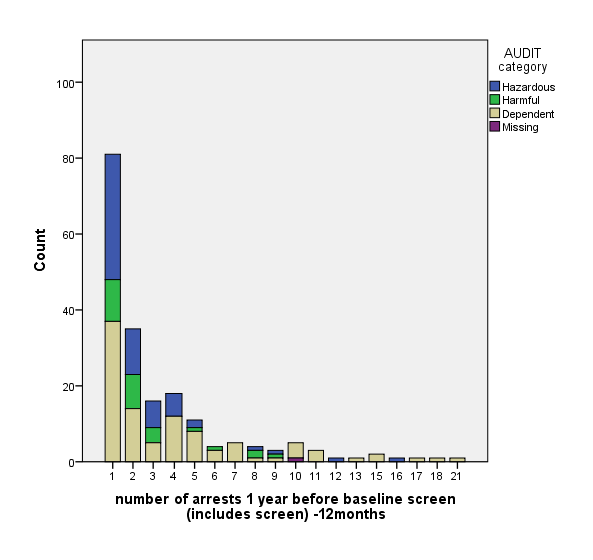

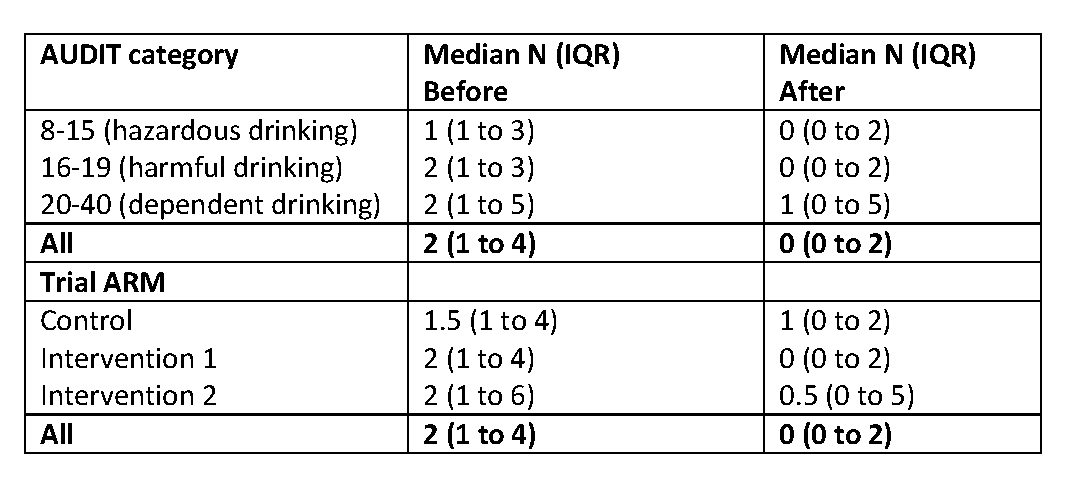

Arrest data are shown below, displayed by drinking category: values ranged from 1-21 arrests in the year before the trial and 0-19 re-arrests in the 12 months following intervention. Data were highly skewed and so median values were calculated by trial arm/drinking category.

Domestic violence or abuse (DVA) seemed low (0.5%)After discussion with our TSC, we re-checked the paper records for all 205 trial cases and confirmed our data were correct based on what was written by staff. It is not clear if DVA arrestees were diverted away from the study or if detention staff did not approach these individuals.

Economic Evaluation: The main aim was to determine the feasibility of methods used to collect cost and outcome data from arrestees. This was assessed by the proportion of missing responses on questionnaires (including service use and EQ-5D). Self-reported responses by arrestees in the trial at 12 months (26% cases) were over 90% across all items in all three trial arms. This suggests that the questionnaires used to collect data in the pilot trial are a feasible method for arrestees and could be used effectively in a full trial. We did not systematically collect resource data linked staff time inputs (training, screening or intervention delivery). For a full trial, these data would need to be collected using procedures established in other criminal justice trials [3].

Conclusions

The need for alcohol intervention in police settings was confirmed by finding that 54% of screened arrestees were identified as having alcohol-related risk or harm (AUDIT score 8+); this is more than twice the general population rate. Half of these individuals were potentially alcohol dependent (AUDIT score 20+) and likely to require further assessment and potentially specialist care. These results are in line with other work in police settings [4].

In this pilot trial, we successfully recruited to target in all 3 trial arms and staff delivered screening and brief advice to 100% cases. However, just 18% of relevant participants received brief counselling (intervention 2). Primarily if this occurred on the same day as screening. Retention of arrestees was also challenging and just 26% of cases were followed up at 12 months, our primary outcome measurement point. Loss to follow-up was mainly due to participants moving address, changing their (mobile) telephone numbers or sometimes giving erroneous contact details. Four participants were in prison when we re-contacted them at follow up, and one died during the study (as reported by a family member). In general, it was not always possible to establish if an individual was uncontactable or reluctant to be contacted. We were not able to offer financial incentives to encourage participation in the trial as senior police staff were unhappy with this approach. In PPI and interview work there were a range of views on this issue; suggestions were made about other possible incentives for a future trial including: vouchers (e.g. shopping, food, mobile phone, transport), time out of their cell in custody, or a certificate of participation in the research study.

Qualitative interview work indicated that trial processes seemed to be broadly acceptable to both staff and arrestees, and most participants engaged positively with the study intervention and procedures. Arrestees reported a range of reasons for participating in the study; some to alleviate boredom whilst in custody although others were positive about the opportunity to think about why they had been arrested and how this might change. We identified a number of issues that would require further attention in any potential future work. Firstly, staff training would need to be enhanced to ensure clarity about some study processes including recruitment/consent processes. In addition, both staff/arrestees were sometimes confused about the difference between trial procedures and intervention activity; some felt that follow-up was part of the ‘brief intervention’ and wondered why it was left as late as 6 or 12 months after the initial input (data not presented).

Routinely measured data were available for most participants; 94% gave permission for their police data to be accessed and we obtained arrest data for 93% of these cases. These data provided rich information about numbers of arrests and types of offences. During interview work, arrestees were positive about the idea of giving consent for health data to be accessed as well as being re-contacted for further details about their, as one arrestee stated: “If you need further stuff then I’m, yes, fine to contact me”. Linking up health and arrest data was also viewed as being acceptable in our PPI work. With the correct governance approvals in place, plus details of participant names, dates of birth, gender and postcodes we are optimistic about future linkage to NHS data via GP/hospital records.

Taking all outcomes together, we have mixed findings regarding the feasibility of a full trial. A definitive evaluation is feasible on the basis of: positive staff and arrestee recruitment; the successful delivery of screening and brief alcohol intervention, as long as this occurs on the same day as screening; and reported acceptability of study procedures. Thus we feel that a two-armed trial would be most efficient, however, whether the precise intervention content should be brief advice or brief counselling would need to be explored further. In addition, intervention outcomes would need to be measured via routinely collected data such as impact on arrests and/or use of health services (e.g. A&E presentation) rather than alcohol consumption per se. The latter would require direct follow-up of participants which results in too high attrition to ensure a low risk of bias. However, processing arrests and responding to emergency department presentations are key public sector service measures with significant resource implications. There is also a known link (with intoxication as the mechanism of action) between heavy alcohol use and offending behaviour [3] plus A&E presentations [5]. We are currently discussing, as a team, the most appropriate primary outcome measures and likely sample size required in a future definitive trial based on our own and other salutogenic evaluations in the criminal justice field [6] [7].

References:

- Birch J, Scott S, Newbury-Birch D, Brennan A, Brown H, Coulton S, Gilvarry E, Hickman M, McColl E, McGovern R, Muirhead C, Kaner E. A pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the police custody setting (ACCEPT): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Pilot and Feasibility Trials 2015, 1:6, DOI 10.1186/s40814-015-0001-7

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): The WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with hazardous alcohol consumption. II. Addiction 1993; 88:791-804.

- Newbury-Birch D, Coulton C, Bland M, Cassidy P, Dale V, Deluca P, Gilvarry E, Godfrey C, Heather N, Kaner E, McGovern R, Myles J, Oyefeso A, Parrott S, Patton R, Perryman K. Phillips T, Shepherd J, Drummond C. Alcohol screening and brief interventions for offenders in the probation setting (SIPS Trial): a pragmatic multicentre cluster randomised controlled trial. Alcohol and Alcoholism 2014, doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu046

- Brown N, Newbury-Birch D, McGovern R, Phinn E, Kaner E. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in a policing context: a mixed methods feasibility study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29:647–54.

- Parkinson K, Newbury-Birch D, Phillipson A, Hindmarch P, Kaner E, Stamp R, Vale L, Wright J, Connolly J. Prevalence of alcohol-related attendance at an inner-city Emergency Department and its impact: A dual prospective and retrospective cohort survey. Emergency Medicine Journal 2015; Doi:10.1136/emermed-2014-204581

- Sherman LW, Strang H, Barnes G, Woods DJ, Bennett S, Inkpen N, Newbury-Birch D, Rossner M, Angel C, Mearns M, Slothower M. Twelve experiments in restorative justice: the Jerry Lee program of randomized trials of restorative justice conferences. J Exp Criminol (2015) 11:501–540. DOI 10.1007/s11292-015-9247-6

- Baldwin SA, Murray DM, Shadish WR, Pals SL, Holland JM, Abramowitz JS, Andersson G, Atkins DC, Carlbring P, Carroll KM, Christensen A, Eddington KM, Ehlers A, Feaster DJ, Keijsers GPJ, Koch E, Kuyken W, Lange A, Lincoln T, Stephens RS, Taylor S, Trepka C, Watson J. (2011) Intraclass correlation associated with therapists: estimates and applications in planning psychotherapy research. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40 (1), 15-33.doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.520731.

Dissemination

Published Articles

Protocol paper published in Pilot and Feasibility Studies:

Birch J, Scott S, Newbury-Birch D, Brennan A, Brown H, Coulton S, Gilvarry E, Hickman M, McColl E, McGovern R, Muirhead C, Kaner E. A pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the police custody setting (ACCEPT): study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 2015; 1:6 DOI 10.1186/s40814-015-001-7

Planned publications

ACCEPT: A pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the police custody suite setting: main study findings. Michelle Addison et al. Target journal to be decided.

Brief Interventions with detainees with alcohol use disorders in the police custody suite: a qualitative study of custody staff role security. Ruth McGovern et al. Target journal to be decided.

Presentation of self and ‘playing the game’ in the police custody suite setting: Findings from qualitative interviews with arrestees in a pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention (ACCEPT. Michelle Addison/Ruth McGovern et al. Target journal to be decided.

Exploring the intersections between Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPS) and other substance use in a police custody suite setting in the North East of England. Addison et al. Drugs, Education, Prevention and Policy (under review)

Conference papers

Addison M and Crowe L. Findings from a pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the police custody suite setting (ACCEPT), Presentation at the North East Crime Research Network, Northumbria University, 7th April 2016

Kaner et al. ACCEPT – A pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the police custody suite setting. Poster at the SPHR Annual Scientific Meeting (19th March 2016), Centre for Life, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Kaner et al – ACCEPT - A pilot feasibility trial of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the police custody suite setting. Presentation at PHE Conference (Sept 2016)

Addison et al. 2016 – ‘The impact of Novel Psychoactive substances in the police custody setting’ - Novel Psychoactive Substances Conference Newcastle, Nov 2016 - Partnership between Fuse, PHE NE and Newcastle University to organise NPS event, ‘Exploring NPS Use and its Consequence’ Nov 2016. 100+ delegates from service providers and third sector. Organisations include NHS, PHE, CCGs, range of universities, police forces, prisons, Banardoes, Changing Lives, Lifeline, homeless networks

Addison et al. NPS - ‘Exploring the intersections between Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPS), alcohol and other substances for police practitioners and arrestees in a custody suite setting in the North East of England’, Drugs and Toxicology Conference: The Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences, March 2017

Addison et al. ‘The intersections of NPS and other substances within police custody’ - Evidence-Based Policing – Research Showcase, College of Policing, Coventry, May 2017.

Kaner et al. 2017 - Blurring the lines of responsibility in emergency services: when does partnership end and dependence begin? Seminar organised by the Institute for Local Governance, Teesside University, 23rd June 2017, 9.30 – 1.00.

Plain English Summary

There is a link between alcohol use and offending behaviour. Alcohol has been found to be a factor in half of all violent crimes and around a quarter of police time is spent on alcohol-related incidents. The use of brief alcohol advice or brief counselling can help people reduce heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems. However, most studies have been carried out in health settings. The purpose of this study is to find out whether it is possible to use similar alcohol advice or counselling approaches in police custody suites with people who have been arrested.

We did a small pilot study to see if staff based in police Custody Suites can identify arrested people who are also heavy drinkers and deliver brief advice or brief counselling to them. To see if advice or counselling might help reduce heavy drinking, we tried to contact the drinkers after one year to measure any effects. We also asked if the study was acceptable to staff and arrestees.

All arrestees completed a short questionnaire about their drinking and those who were heavy drinkers were placed in one of three groups:

- Some received no advice or counselling about alcohol.

- Some were given 10 minutes of brief advice about their drinking from detention staff.

- Some received this advice about their drinking from detention staff and were also offered 20 minutes more counselling from a trained counsellor either straight away or on another day.

We aimed to recruit 60 arrestees in each group (180 in total), provide advice or counselling to all relevant people and re-contact at least half of them a year later.

We recruited 79 (group 1); 65 arrestees (group 2) and 61 (group 3). Everyone received the brief advice but only 18% received the brief counselling. We were able to re-contact just 26% one year later, mainly by telephone.

However, most (94%) arrestees gave us permission to ask the police for information about their arrests in the year before and after the study. This let us find out who was arrested in the year before and after they took part in the study – and how many times arrests occurred.

We concluded that that we could recruit the right numbers for a future study and the Custody Suite Staff can provide advice - but not the extra counselling – especially if this was on a different day. The staff and arrestees told us that they found being part of the study acceptable. As we could not re-contact most of the arrestees one year later, we decided it would be best to use police information (on arrests) and also NHS information (such as visiting A&E units) to see if the advice was helpful to arrestees rather than trying asking arrestees themselves.

Public Involvement

We conducted extensive PPI work with over 30 stakeholders which has focused on obtaining views about the trial concept, the study documents, the intervention itself (including setting and providers), and follow up procedures, data linkage plans and incentivisation.

Organisations involved in PPI discussions include: Lifeline – a service provider for those with alcohol issues in Sunderland; The People’s Kitchen; CLINKS (Clinks supports, represents and campaigns for the voluntary sector working with offenders); Newcastle Civic Centre - Service Use Involvement Officer; Service providers of brief intervention; representative from P.R.O.P.S (Scotswood Family Drug Support Group).

The study itself was well received by organisations and individuals. It was felt it should be made explicit that everyone passing through the custody suite is approached by Custody Suite Staff. Even for those who do not engage beyond the initial contact, the study was viewed as ‘planting the seed’ for change. The exclusion criteria of ‘serious mental health’ was raised as a concern by some groups; individuals felt that what constitutes ‘serious mental health’ should be made clearer in a future trial. Service providers stated that some participants might not want to be re-contacted during the follow up period (for example, may be a reminder of a difficult time). If researchers were engaged with a range of services within the city during the research it may help reaching people with no fixed addresses (for example, the People’s Kitchen). The consensus was that accessing re-arrest data and health data in a future trial would not be an issue for potential participants. Incentivisation for participation received mixed views however, with concern resting on the incentive perhaps exacerbating an existing substance use problem. However, it was felt it might improve participation and follow up rates in a full trial.

Impact

We have presented this work to a wide range of policy makers in the Department of Health, PHE and the Home office. We are in discussions with them about the feasibility of a full trial.

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Public Health Research (SPHR-SWP-ALC-WP2)

Department of Health Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR School for Public Health Research, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.