Can Metaphors usefully represent underlying cognitive behaviour therapy principles

Can metaphors usefully represent underlying cognitive behaviour therapy principles for medically unexplained symptoms and how acceptable are such generic and MUS-specific metaphors to patients and practitioners?

254

21 August 2017

02 March 2016

30 June 2017

15 months

Medically unexplained symptoms, cognitive behaviour therapy, qualitative, primary health care, secondary health care, mental health

-

Professor Athula Sumathipala, Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University

- Research Department of Primary Care & Population Health, University College London

- Professor Carolyn Chew-Graham – Co-investigator, Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University

- Dr Tom Kingstone – Research Associate,Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University

- Dr Tom Shepherd – Study Coordinator, Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University

- Dr Heather Burroughs – Co-applicant, Research Institute for Primary Care & Health Sciences, Keele University

- Jane Mason – Administrator, Project Support Keele University

- Clark Crawford – Study Sponsor Representative, Research Governance, Keele University

- Adele Higginbottom – Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement representative

- Dr Marta Buszewicz – Co-applicant, Research Department of Primary Care & Population Health, University College London

Project objectives

There are three primary objectives:

To explore the acceptability of metaphors to people with MUS (Medically Unexplained Symptoms) and practitioners who manage people with MUS.

To achieve consensus among practitioners (GPs, IAPT therapists, psychologists and psychiatrists) and people with MUS on the appropriateness of the metaphors discussed.

To agree a series of metaphors to be central in the development of an intervention which could be tested in an acceptability and feasibility randomised controlled trial.

Brief summary

Changes to the original project proposal

During the course of the study two substantial amendments were submitted to the East of England Cambridgeshire and Hertfordshire NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC). The research team also experienced recruitment challenges that impacted study timelines and recruitment targets; as a consequence some of the data collection activities were not feasible.

Further information is provided below.

Amendment 1 (SA1)

The original study protocol included focus groups only for data collection involving healthcare practitioners. An amendment was submitted to the NHS REC (31 May 2016) and approved (27 June 2016)

Amendment 2 (SA2)

The original study protocol outlined consensus groups for healthcare practitioners and people with MUS only. In light of recruitment challenges experienced with arranging focus groups and one-to-one interviews, the research team altered the protocol to include academics/academic clinicians as participants in the consensus group phase of the project. An amendment was submitted to the NHS REC (21 November 2016) and approved (09 February 2017). Objective two changed as a result of this change in methodology: To achieve consensus among practitioners (GPs, IAPT therapists, psychologists and psychiatrists), people with MUS and academics/clinicians with an interest in MUS research on the appropriateness of the metaphors discussed.

Recruitment challenges

The focus group method became unfeasible for several of the healthcare practitioner types due to constraints on their time imposed by workload pressures. This informed the research team’s decision to submit a substantial amendment (SA1) (as described above) to grant additional flexibility for potential participants. Difficulties were experienced in recruiting IAPT practitioners for focus groups and one-to-one interviews do to their concurrent work pressures. The research team actively engaged with service leads at South Staffordshire and Shropshire NHS Foundation Trust to overcome this; however, recruiting these individuals remained challenging. The research team also experienced difficulties recruiting people with MUS. The recruitment strategy comprised a poster that required individuals to self-identify as experiencing MUS. The poster was displayed widely (i.e. pharmacies, public buildings, and GP practices as arranged by the Clinical Research Network). However, the research team received a low response rate. Furthermore, for those who did express an interest in participating, non-attendance was common. The recruitment challenges resulted in a no-cost extension to the study, which was granted in June 2016.

Consensus groups were not feasible

The recruitment challenges and subsequent study drift had implications for conducting consensus groups. Recruitment challenges continued in attempts to schedule consensus group meetings. An academic researcher/clinician consensus group arranged for April 2017 was cancelled due to non-availability of invited participants, and the rescheduled meeting in June 2017 was also subsequently cancelled for this reason. There were insufficient numbers to conduct consensus methods with people with MUS.

Methods

Focus groups and 1-to-1 semi-structured interviews were conducted with people with medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) and practitioners who manage the care of people with MUS. These were held either at the Research Institute for Primary Care Research, Keele University or South Staffordshire and Shropshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (SSSFT) of participant’s place of work depending on convenience to participants. TK conducted all interviews and focus groups; AS supported facilitation of two focus groups. At the start of each focus group/interview TK obtained written consent from participants, data collection activities were digitally recorded and transcribed for analysis. Thematic analysis and content analysis were conducted to maximise the collected data; this was led by TK. AS, CCG, MB, HB, and TS contributing to refinement of analysis in two designated meetings.

Findings

Three focus groups and 13 1-to-1 interviews were completed with: 7 Psychiatrists, 6 GPs, 5 people with MUS, 5 Psychologists, and 3 IAPT (‘Improving Access to Psychological Therapies’) practitioners. Key themes were identified from the thematic analysis around the experience of living with and managing MUS, these included: MUS does not fit a neat box, going round in circles, stigmatisation and emotional neglect [these will be reported in the main findings paper, discussed below as part of dissemination]. The findings related to the three objectives are summarised under the following sub-headings.

Objective 1: To explore the acceptability of metaphors to people with MUS and practitioners who manage people with MUS

All HCPs described using metaphors and analogies in clinical practice to support explanation of symptoms to patients and clinical concepts: “Metaphors are a core part of our communication skills in explaining different difficult concepts” [Psychiatrist 03]. Typically, metaphors were either learned through informal processes (e.g. shadowing a colleague) or self-conceived, and used “more off the cuff than rehearsed” [Psychologist 01] to fit a natural conversation flow. Healthcare practitioners indicated that it would be useful to have a toolkit of metaphors to refer to. However, it was acknowledged that it is not a case of: “one-metaphor-fits-all” [Psychologist01]. An IAPT worker described their work with patients with long term conditions: “We run groups. You’ll use a metaphor and half the people are nodding and half the people are looking a bit like, ‘What?’” [IAPT 02].

People with MUS shared a concern about introducing new metaphors suggesting that they: “run the risk of even more confusion to the patient” [PwMUS 01]. However, they themselves would use metaphors or similes to describe their symptoms (e.g. the noise of a headache being ‘like a choke on a motorbike or a chainsaw’ [PwMUS 02]). Therefore, in general metaphors provide an important function in communication between patients and healthcare practitioners. It is important when developing metaphors to ensure that they are simple and fit for purpose; however, there may not be a ‘one-size-fits-all’ metaphor so therefore having different options is necessary.

Objective 2: To achieve consensus among practitioners (GPs, IAPT therapists, psychologists and psychiatrists), people with MUS and academics/clinicians with an interest in MUS research on the appropriateness of the metaphors discussed

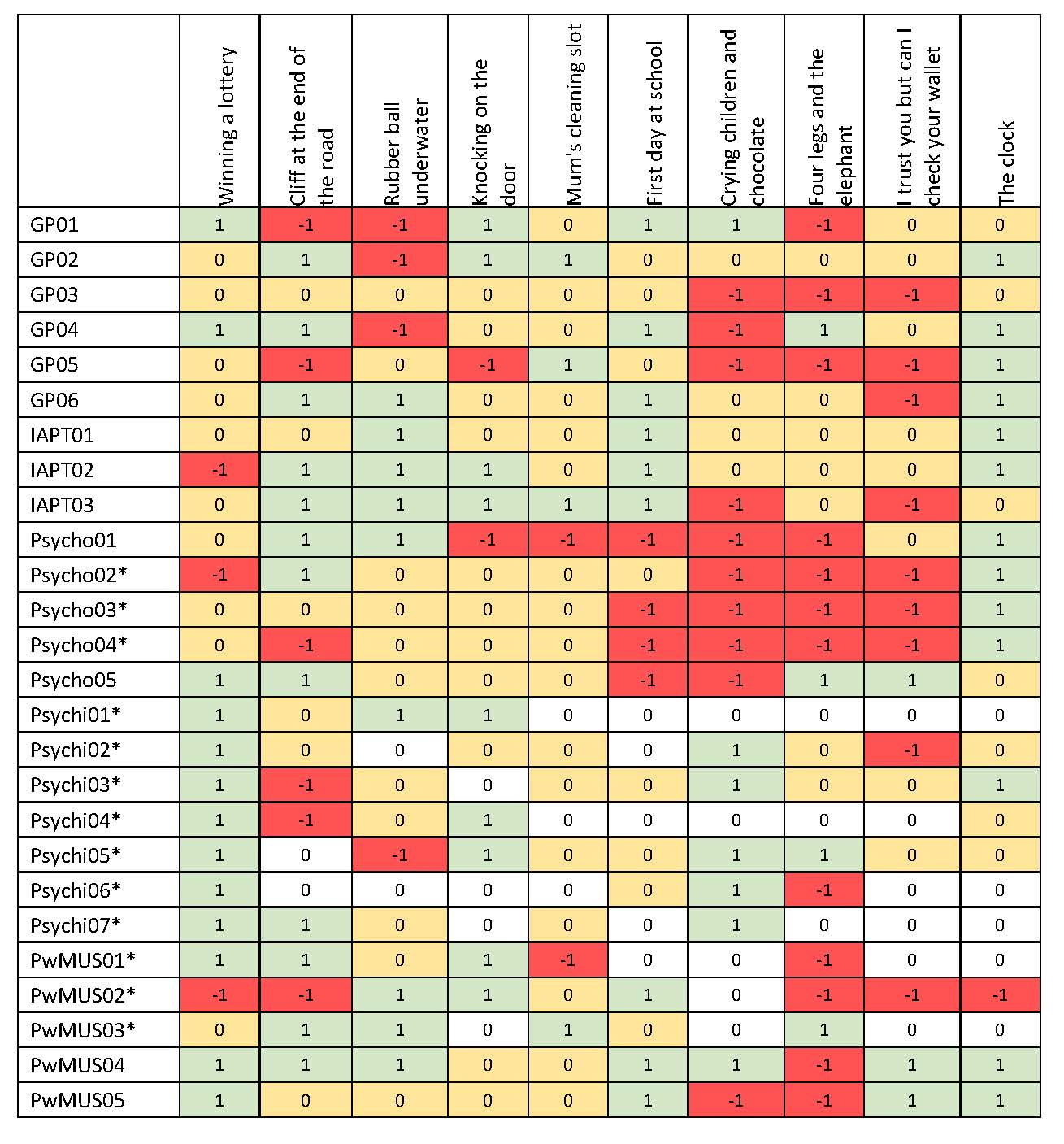

Each of the metaphors was described and discussed during interviews with the mixed participants. Participants were asked if the metaphor was understandable (healthcare practitioners were also asked if they would use the metaphor in practice). Through content analysis, the views of participants were converted into numerical values to aid summary, as presented in Table 1 (next page). A score of 1 = a wholly positive response; 0 = mixed response (positive and negative); -1 = negative. Scores are colour coded to support interpretation. Participants also provided suggestions to improve each of the metaphors; indicating that all metaphors can be improved upon. The ‘winning the lottery’ and ‘the clock’ metaphors received the most positive responses (12). In contrast, the metaphors ‘crying children and chocolate’, ‘four legs and the elephant’, ‘I trust you but can I check your wallet’ require significant changes.

Table 1. Summary table of content analysis on metaphors

*Participant took part in a focus group and so may not have provided an individual view on metaphor

Objective 3: To agree a series of metaphors to be central in the development of an intervention which could be tested in an acceptability and feasibility randomised controlled trial

Findings from the interviews and focus groups indicated a need to undertake further development work to refine and improve the current set of metaphors, developed in Sri Lanka, before a series of metaphors can be agreed for an intervention.

Conclusions

This study has considered multiple perspectives from people with MUS and a diverse mix of HCPs to identify the persistent challenges in managing MUS in primary and secondary care. The stigmatisation of people with MUS (or suspected MUS) has negative implications for patient care as does the stigmatisation of psychological services by GPs. The tortuous process of diagnosis can lead to anxiety and frustration for HCPs and people with MUS alike. However, people with MUS described being in vulnerable situations living with unexplained symptoms desperately searching for answers. A need is evident for MUS-specific interventions to be developed to support patients to live with their persistent symptoms, and the unknown nature of these symptoms, during the long diagnostic process. Metaphors are a core component of patient-practitioner communication; however, it seems there may not be such a thing as a one-size-fits-all metaphor to use with people with MUS. The metaphors reviewed in this study represent a first step in the development of a new intervention; although further developmental work is required to adapt the metaphors used in Sri Lanka to be appropriate for UK clinical practice. The findings provide further support for collaborative care approaches that involve General Practice and Psychological services.

Plain English summary

Background:

Medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) are symptoms that cannot be explained by an alternative medical diagnosis despite adequate investigations. MUS are a challenge for health care services and account for up to 40% of new consultations occurring in UK primary care settings. Living with and providing clinical care for people with MUS can have widespread negative impacts affecting patients, their families, and healthcare practitioners. Evidence suggests that psychological therapies may provide effective treatment and these treatments are highlighted in positive practice guidelines produced by the NHS. However, access to psychological therapies is restricted by a lack of formal training among primary healthcare practitioners and reluctance from patients to accept psychological therapy. An intervention using metaphors to explain complex psychological principles has been trialled in Sri Lanka for people with MUS. The appropriateness of these metaphors has not been assessed in the UK before.

Aim:

This study sought to explore the acceptability of metaphors, developed in Sri Lanka, to explain psychological principles for people with MUS and those who manage their care in the UK.

Research design and setting: Interviews and focus groups with healthcare practitioners (HCPs) from both primary and specialist care and people with MUS in Staffordshire and Shropshire. Interviews and focus groups took place at Keele university or at the healthcare practitioner’s place of work. Consent to digitally record interviews/focus groups and type these up was obtained at the start of the interview/focus group. Topics discussed during interviews/focus groups included: understandings of MUS, experience of living with/managing MUS, and views on metaphors.

Results:

Twenty-one HCPs (7 psychiatrists, 6 general practitioners, 5 clinical psychologists, 3 psychological therapists) and 5 people with MUS completed interviews/focus groups. Key themes were identified including: MUS does not fit into a neat box, going round in circles, stigmatisation and emotional neglect. All participants provided views on the metaphors and considered the use of metaphors acceptable; however, not all the metaphors suggested were considered appropriate by all participants.

Conclusions:

The perspectives of different healthcare practitioners explained challenges to diagnosing MUS, subsequent barriers to accessing care, and the complexity of the treatment pathway for people with MUS. Our findings will inform further development of an intervention using metaphors to explain CBT principles potentially used by psychological practitioners.

Dissemination

Published articles

Published an editorial in the British Journal of General Practice: Chew-Graham, C. A., Heyland, S., Kingstone, T., Shepherd, T., Buszewicz, M., Burroughs, H., & Sumathipala, A. (2017). Medically unexplained symptoms: continuing challenges for primary care. British Journal of General Practice; 67 (656): 106-7.

Planned Publications

A main findings paper is currently being drafted by the research team. The manuscript is entitled: Exploring acceptability of metaphors to explain cognitive behaviour therapy principles for people with medically unexplained symptoms: a qualitative study. The target journal is the British Journal of Health Psychology. The manuscript is due to be submitted by the end of August 2017.

Presentations

The findings from this research study have been presented at the following conferences:

- Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) annual conference – June 2016 – a poster presentation and workshop for practitioners were delivered during the conference.

- North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) annual conference – November 2016 – preliminary findings were presented at this conference.

- Society for Academic Primary Care (SAPC) annual conference – July 2017 – the main findings were shared in an oral presentation.

- School for Primary Care Research Showcase event – Sept 2017 – poster presentation of main findings will be shared.

Project website: https://www.keele.ac.uk/pchs/research/mentalhealth/musmedunexplainedsymptoms/

Public involvement

The patient and public involvement (PPI) team at Keele University supported PPI during this study. People with medically unexplained symptoms (e.g. chronic low back pain) were recruited from existing members of the Research User Group at Keele University. PPI members provided input on the study logo, study design and recruitment process, and development of patient facing documents. The preliminary findings from the analyses were shared with PPI members.

Impact

The research team are currently developing a proposal for a feasibility study to conduct further development a complex intervention (involving primary care and psychological practitioners) using metaphors informed by the findings of this research.

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research (project number 254 )

Department of Health Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIHR School for Primary Care Research, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.